The US economy is facing payback today for the 2009-10 scramble to jump-start the economy. And there is now an urgent need to create demand, says SouthBay’s Andrew Zatlin.

“Putting aside dogmatic discussions about the nature of recessions, the reality in 2009 was that supply chain inventory levels were too high,” argues, Andrew Zatlin, founder of Silicon Valley-based economic research analysts, SouthBay Research.

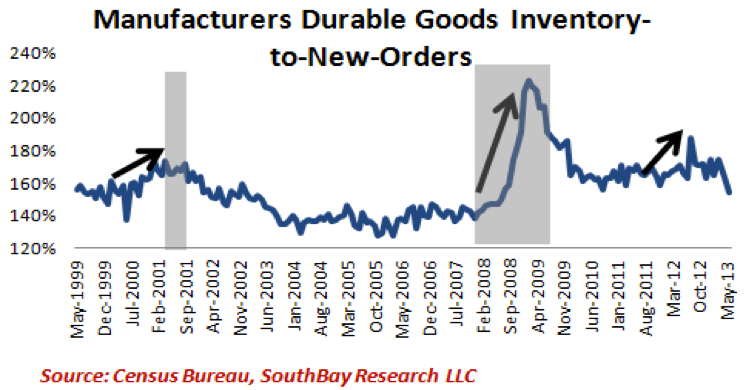

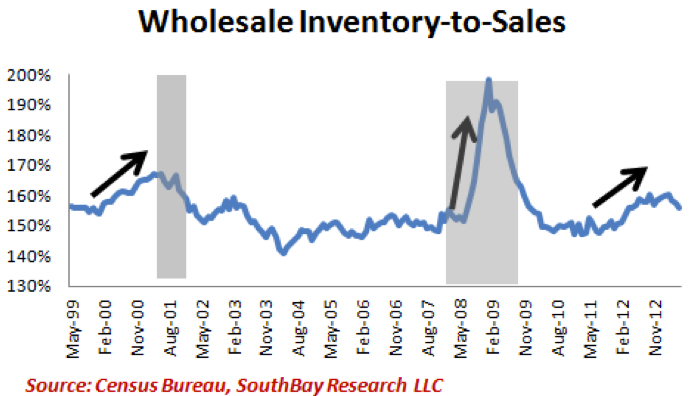

He points to movements over the last fifteen years in both the Manufacturers Durable Goods Inventory-to-New-Orders and Wholesale Inventory-to-Sales as evidence of these overly high supply chain inventory levels.

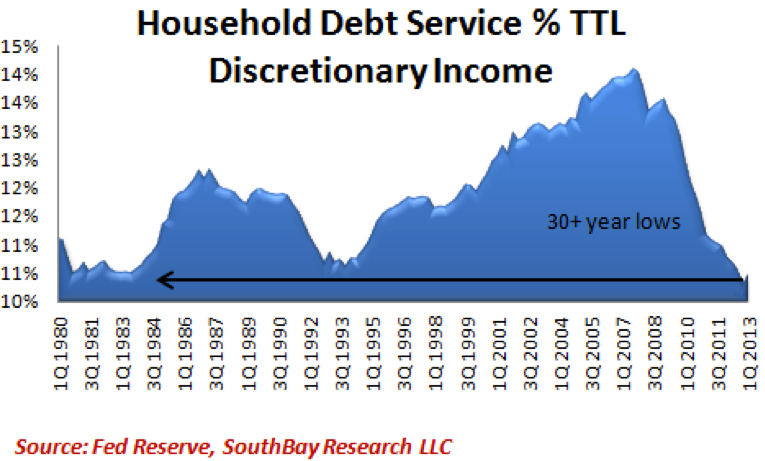

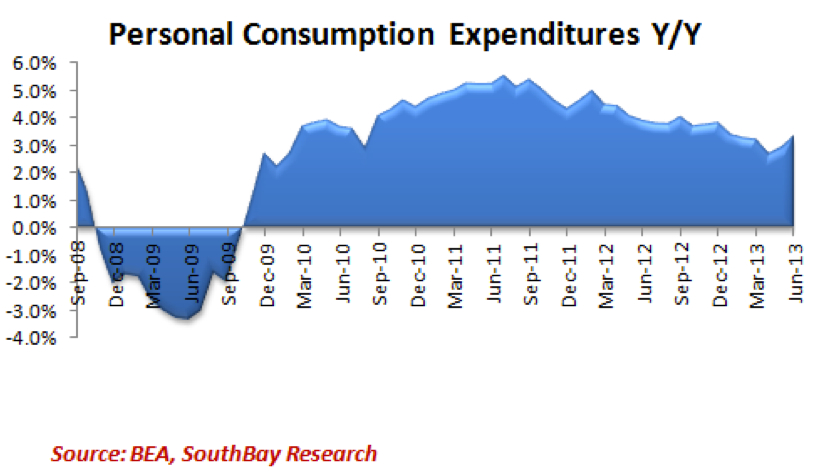

Zatlin says the Fed’s extremely loose monetary policies helped Wall Street and households to improve their balance sheets, pointing to thirty-year lows in household debit service as a percentage of total discretionary income, and personal consumption expenditures.

In addition, fiscal stimulus came in the form of the 2008 Economic Stimulus Act.

“Besides other treats (like raising depreciation limits and equipment spending caps), the most important part of the Act was to accelerate depreciation by 50 per cent — buy today and immediately get to write off 50 per cent,” says Zatlin.

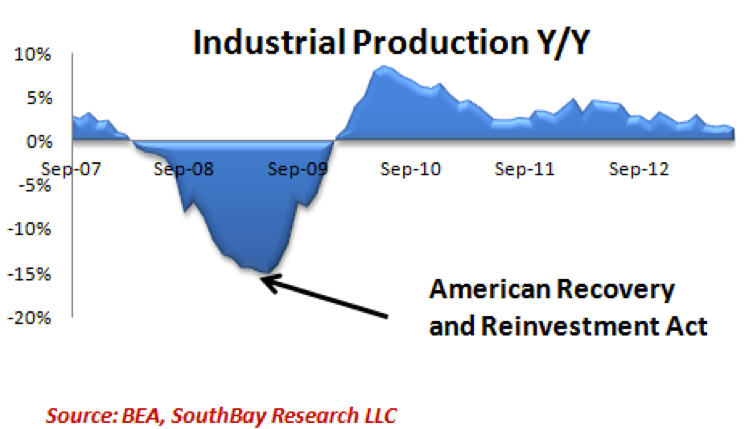

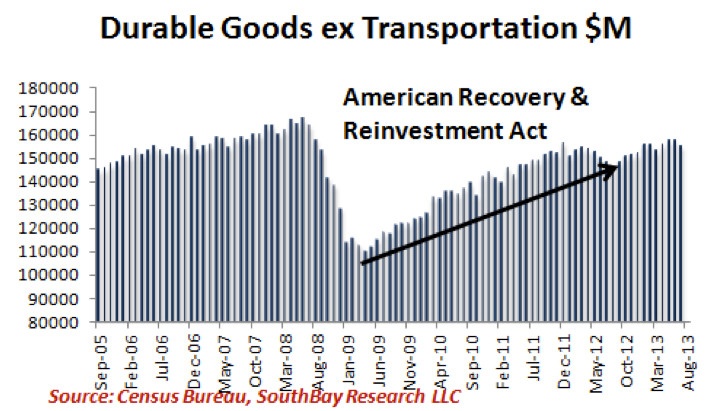

But the 2008 stimulus wasn’t enough. So 2009 brought the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, repeating the 2008 accelerated depreciation measure and adding $787 billion in spending.

“The impact was immediate,” says Zatlin. “Manufacturing immediately turned around. As did Business CAPEX spending.”

The 50 per cent depreciation was extended again in 2010 with the Small Business Jobs and Credit Act of 2010 — “That’s three years in which businesses enjoyed unprecedented incentives to replace factory equipment,” says Zatlin.

But that was then, this is now — the replacement cycle is disrupted

Zatlin explains that depending on the asset, US tax codes allow for either a five- or seven-year depreciation cycle. But for factory equipment, depreciation can be as brief as three years: “In other words, four-and-a-half years after the 2009 Act, we should be witnessing a major surge in factory spending as amortised equipment gets replaced. Instead, spending is slowing.”

Zatlin thinks that part of the reason for this seemingly counterintuitive movement is timing. Instead of staggered replacement, US industry replaced much of its equipment all at the same time.

“Another factor is global over-supply; last year Inventories-to-Sales and Inventory-To-New-Orders shot up to recessionary levels,” he says. “That’s why the Fed panicked in 4Q12. An entrenched cyclical downturn is evident across all suppliers, such as Alcoa and Caterpillar.”

While the world seems to be breathing collective sighs of relief that Europe and China may start buying again, Zatlin warns that it’s all relative. He explains that each month the supply chain is responding to business efforts to align inventories and sales.

“It’s like watching a drunk driver zig-zag from one side of the road to the other. One month there’s too much inventory drawdown, the next too little,” says Zatlin. “New Orders will pop up one month as everyone compensates, only to adjust down the next. With the economy clearly on a downtrend, forward investing will be restrained.”

For Zatlin, the key point is that macro signals will be responding more and more to the replacement cycle disruption: “It’s really only just beginning. It will peak in 2014 — five years after the 2009 Act.”